I awoke in the lone darkness of the tent, not sure what bothered me more — the freezing temperature of the February night or the loud howling that sounded like coyotes roaming the mountain. I reached for the phone; it was almost two. Five more hours until sunrise.

Shivering, I put on the only remaining garment I had saved up and crawled back into my sleeping bag, assuring myself in half-awake naivety: I’m on holy land; no way coyotes gonna eat me here!

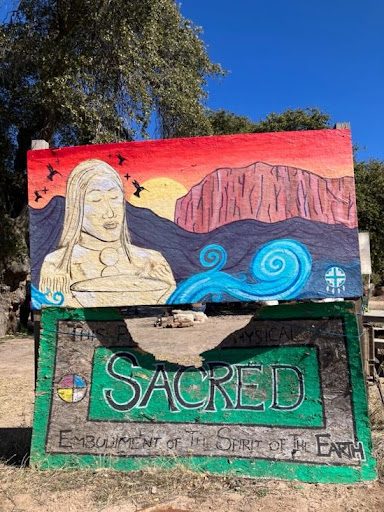

I was at Chi’chil Biłdagoteel, the sacred site of the Apaches. Known in English as Oak Flat, it’s a beautiful place just about an hour’s drive east of Phoenix.

My night terrors aside, there is real danger hanging over Oak Flat. However, it doesn’t come from wild animals but from humans who have gone wild in the pursuit of profit.

Deep beneath the rusty desert soil that is shaded by silvery green oak trees, the Earth holds a vast deposit of copper. It is the third largest in the world. Since its discovery in the nineties, Oak Flat has become a battleground of conflicting interests and a hotbed of Native American struggle for religious rights.

This ongoing battle is what brought me to Oak Flat. I am part of a student film team working on a short documentary about young Native Americans who joined the Prayer Run to spread awareness and advocate for Oak Flat preservation.

The stakes are high here.

On the one hand, foreign-owned mining giant Resolution Copper has tried hard and lobbied generously to win the right to mine copper for the next 40 years, creating jobs and boosting Arizona’s economy while leaving a trail of water and land pollution and irreversible damage. Resolution’s parent company, Rio Tinto, is infamous for barbaric business practices around the world, sometimes even leading to war.

On the other hand, Native American tribes are trying to save the site from destruction, supported by environmental activists and many concerned citizens. The Oak Flat mining method involves digging tunnels under a copper deposit, then blasting ore and taking it away, causing the ground to collapse. It will leave a huge crater deep enough to hold the Eiffel Tower.

For Apache, their religion is under threat. Since time immemorial, indigenous tribes have considered Oak Flat a sacred place where spirits reside, coming-of-age ceremonies are held, medicine plants are gathered, and other spiritual practices are performed.

To defend Oak Flat, Apache Stronghold has filed a case against the United States, which is currently at the appeals court and could eventually reach the Supreme Court. Basically, the tribe is asking not to mine their church — it is no less holy just because it has no walls, altar, or spire. Would you mine Mount Sinai? Indigenous peoples are taking this question to Congress, the court, and all nations.

We may never know if Rio Tinto would stay away from mining Mount Sinai, but Oak Flat is definitely in trouble. Currently, it remains public land, but the government has approved giving it to the mining company through a controversial act of Congress that more than a million people protested. A recent poll shows that 75% of Arizona voters oppose Resolution Copper’s mine at Oak Flat. While the land swap still hasn’t gone into effect, it could happen any time this summer.

Recently, Humphrey Fellows had the opportunity to meet with US Senator Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, so I asked her if she really supports mining at Oak Flat, which will lead to the destruction of the Apache sacred land. She gave a well-polished non-answer, calling for balancing the nation’s interest in green energy development with the need to respect Native American heritage. Well, you can’t mine Oak Flat and protect it at the same time unless you fall back on some Orwellian doublespeak about “destruction out of respect.”

As a Latvian, I feel deeply connected to the Apache’s unique ties to their land. Nature in my traditional culture is celebrated as a realm where human and divine lives are inextricably linked.

In our ancient mythology, the Tree of Dawn connects Heaven and Earth as the Axis Mundi. My ancestors performed their rituals in sacred oak groves. There are still around 20 thousand ‘monumental trees’ in Latvia, which are protected by the state due to their age and magnificence. We have our traditional, centuries-old folk song that advises: “Walking through the silver grove, I didn’t break a single twig.” Latvians still celebrate nature rites, even after centuries of Christianity. We live a modern life, but nature has a prominent role in our cultural code, and preserving it for future generations is a crucial task.

That’s why the Apache fight speaks to my heart and mind. Delving into this conflict and Native American heritage has become the most meaningful thing I have undertaken in this entire year of the Humphrey Fellowship. I have met inspiring people, experienced Apache rituals, and learned so much. It is humbling to see young indigenous kids born into this epic battle between spirituality and corporate interests growing into adulthood and reconnecting with their native culture.

American history has decades of horrific crimes against indigenous peoples who have been killed, kept in ghettos on reservations, and deprived of their freedom and identity. Colonizers have come to strip the land of its resources and simply move on to the next place, leaving the wasteland behind. No regrets, just like you don’t care about the empty Coke can thrown in the trash. This unjust colonization battle continues into the 21st century in sacred indigenous places like Oak Flat.

As old legend has it, outnumbered and surrounded by the US cavalry at Oak Flat, the brave Apaches chose death over captivity. They throw themselves off the cliff now named Apache Leap.

Times have changed. Brave Apaches, though still outnumbered, are now fighting for their rights to live and pray freely on their ancestral land. I pray with them.