As if ethical debates weren’t grey enough, Organizational Behavior adds another shade into the monochromatic mix: “Ethical behavior across cultures.”

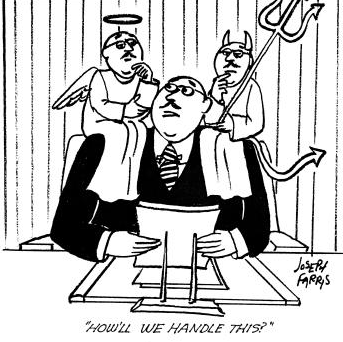

By this point in our academic career, most, if not all of us, have been a part of discussions concerning the moral ‘rights’ and ‘wrongs’ commonly referred to as ethics. Regardless of whether the talks take a normative or applied approach, the result is always the same – there is no black and white answer to ethical dilemmas.

So how do you begin to approach an already challenging subject when you add in the additional challenges of cultural diversity and changing social norms? Not to mention the structural barriers that are formed from the discontinuities between legal and governing systems across cultures.

Then, the discussion takes on even greater importance when you begin to discuss competitiveness and barriers to entry in the marketplace. How can a company from a country that condemns bribery compete with other businesses in countries that condone it? Other ethical debates have to do with labor laws, working conditions and basic human rights issues.

Organizational Behavior suggests there are two ways to approach the problem either by means of cultural relativism or ethical imperialism:

International business behavior is justified on one argument: “When in Rome do as the Romans do.” If one accepts cultural relativism, a sweatshop operation would presumably be okay as long as it was consistent with the laws and practices of the local culture . . . [Ethical imperialism] reflects and absolutist or universalistic assumption that there is a single moral standard that fits all situations, regardless of culture and national location. In other words, if a practice such as child labor is not acceptable in one’s home environment it shouldn’t be engaged in elsewhere (54).

Generally speaking, my view usually falls into the latter category. In the United States, unethical international dealings (by our cultural standards) are morally reprehensible and often hurt the company on domestic soil – drop in consumerism and drop in stock price. But what if the U.S. Company’s consumer base wasn’t operating from domestic soil, what if their market share was in China? Then failing to adapt to Chinese cultural norms could absolutely be detrimental.

Do you think that one approach to international ethics is the right one or at the very least, the lesser of two evils? Should companies, like Donaldson suggests, adopt threshold values that protect “fundamental human rights” and then take other ethical issues on a case by case basis? In other words, how do you deal with cross-cultural ethical dilemmas?

Schermerhorn, Jr., J. R., Hunt, J. G., & Osborn, R. N. Organizational behavior. (7 ed., pp. 50-52). New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

I think the discussion of ethics across cultural boundaries is a fascinating one, especially in terms of journalism. I’ve been taught journalistic “rights” and “wrongs” but never how they might apply differently in other countries besides the U.S. I agree with the view that companies should apply ethical standards on an individual basis after ensuring that universally accepted human rights are being maintained. Because of the possibility of stark differences between cultures, I don’t think it’s possible for a company (or profession, like journalism) to apply an across-the-board code of ethics that applies to each country involved.