Disruptive Innovation

The disruption through innovation seems not to have an end any time soon than ever in history of mankind as man’s ability to grow and tendency to become better can be traced to his either his Creator, God or his “ability to evolved” depending on what he choses to believe.

The disruption through innovation seems not to have an end any time soon than ever in history of mankind as man’s ability to grow and tendency to become better can be traced to his either his Creator, God or his “ability to evolved” depending on what he choses to believe.

If we want to follow the claims of Evolution, man can be seen as moving from one level of development to another through disruptive innovation.

But let’s narrow in on media development or evolution that can be attributed to disruptive innovation. How did we get from the world before the printing press to the world after it?

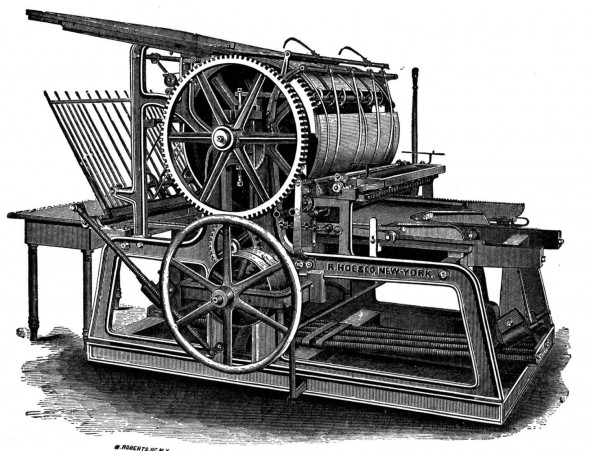

Gutenberg Press

Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg was a German blacksmith, goldsmith, printer, and publisher who introduced printing to Europe. The Gutenberg printing press developed from the technology of the screw-type wine presses of the Rhine Valley. – In 1440, Johannes Gutenberg created his printing press, a hand press, in which ink was rolled over the raised surfaces of moveable handset block letters held within a wooden form and the form was then pressed against a sheet of paper. Johannes Gutenberg press with its wooden and later metal movable type printing brought down the price of printed materials and made such materials available for the masses. It remained the standard until the 20th century.

Gutenberg Bible

Johannes Gutenberg is also accredited with printing the world’s first book using movable type, the 42-line (the number of lines per page) Gutenberg Bible. During the centuries, many newer printing technologies were developed based on Gutenberg’s printing machine, which is said to have opened the doorway for further new innovations in printing. e.g. offset printing. But it took many years to create a major step ahead from the Gutenberg invention – nearly four hundred years!

Elizabeth Lewisohn Eisenstein, an American historian of the French Revolution and early 19th century France, well known for her work on the history of early printing, writing on the transition in media between the era of ‘manuscript culture’ and that of ‘print culture’, as well as the role of the printing press in effecting broad cultural change in Western civilization, wrote, “The Printing Press as an Agent of Change: Volume I: Communications and Cultural Transformations in Early-Modern Europe. It is the first fully documented historical analysis of the impact of the invention of printing upon European culture, and its importance as an agent of religious, political, social, scientific, and intellectual change.

Now in this era of technology, with the old economics destroyed, organizational forms perfected for industrial production have to be replaced with structures optimized for digital data. It makes increasingly less sense even to talk about a publishing industry, because the core problem publishing solves — the incredible difficulty, complexity, and expense of making something available to the public — has stopped being a problem.

In this age of digital web and social media, “Information is increasingly being distributed and presented in real-time streams, (The Stream organizing metaphor for the web for the past several years) instead of dedicated Web pages. The shift is palpable, even if it is only in its early stages,” Erick Schonfeld wrote. “Web companies large and small are embracing this stream. It is not just Twitter. It is Facebook and Friendfeed and AOL and Digg and Tweetdeck and Seesmic Desktop and Techmeme and Tweetmeme and Ustream and Qik and Kyte and blogs and Google Reader. The stream is winding its way throughout the Web and organizing it by nowness.” The Internet’s media landscape is like a never-ending store, where everything is free.

As a result of such disruptive innovation, some are contending that Society doesn’t need newspapers. What society need is journalism. For a century, the imperatives to strengthen journalism and to strengthen newspapers have been so tightly wound as to be indistinguishable. With the level of progress in innovation there needs to be a lot of other ways to strengthen journalism instead.

Main while as new media tools and social networks become more widely utilized, images are delivered directly to the laptops and smartphones of people around the globe, including powerful images of crisis. Far from the scene of unrest or the tumult of a natural disaster, an average person can receive images through Twitter, Tumblr, Facebook, and others, captured by mobile phones or Web-ready digital cameras. Social media has allowed even the least tech-savvy people around the world to become witnesses to history. A whole universe of photojournalists, both amateur and professional, is made available to the public through social networks, allowing news organizations to ferret out important stories using tools beyond their existing technical capabilities. In news organizations around the country, reporters are increasingly expected to provide visuals with their stories. Freelance writers are rebranding themselves as multimedia journalists, and journalism schools, conscious of where the jobs likely will be for their graduates, are training all their students to write and capture audio, photos and video. Its now the era of multimedia Journalism, one in which the reporter should be able to take pictures, do video, audio and write, while the photographer should be able to do all the same. In the midst of such huge disruption, a one in which everyone is a photographer, photojournalism seems to be a must for every journalist. “Visual Journalists Are As Important As Ever”

The annual newsroom census from the American Society of Newspaper Editors showed that jobs for photographers, artists and videographers fell by 43 percent, from 6,171 in 2000 to 3,493 in 2012. By comparison, the number of full-time newspaper reporters dropped by 32 percent, from 25,593 to 17,422 in the same period. Jobs for copy and layout editors and online producers fell from 10,901 to 7,980, a 27 percent loss. The Pew Research highlighted the results this month in a story about the cuts. “Fundamentally, it’s an economic issue, “ said Geneva Overholser, director of the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School of Journalism from 2008 until this year. “We feel deep regret that newsrooms are laying off professional photographers, but in so many of these dilemmas, it’s really essential to think about why we all exist. We exist because we need to fulfill the information needs of the public.” While staff members at smaller newspaper have always worn multiple hats, large newsrooms that used to have the luxury to hire the best writers, the best photographers, the best copy editors and the best graphic designers are now looking for versatile reporters who can do it all. Whether such superhuman journalists already exist or can be trained to do it all—and do it well—is the source of much contention rippling through the industry.

In the midst of this seeming stream of disruptive innovation, many may want to agree with Clay Shirky, an adjunct professor in NYU’s graduate Interactive Telecommunications Program (ITP), that “When we shift our attention from ‘save newspapers’ to ‘save society’, the imperative changes from ‘preserve the current institutions’ to ‘do whatever works.’ And what works today isn’t the same as what used to work.”

Shirky asserts “No one experiment is going to replace what we are now losing with the demise of news on paper, but over time, the collection of new experiments that do work might give us the journalism we need.”

Thomas E. Patterson, author of the 2013 book, “Informing the News: The Need for Knowledge-Based Journalism argues that,” argues that to meet up to the current trend of disruptive innovation, “perhaps the only certainty in journalism is—or ought to be—that the tools you learn how to use today surely won’t remain current for long. On the other hand, requiring students to gain knowledge about well-defined subjects, such as physics, philosophy, economics, and computing, “would move journalism education in an intellectual direction” and would promote an approach that recognizes the value of “knowledge of how to use knowledge.

While G. Pascal Zachary, a professor of practice at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication states, “The creative destruction of journalism as an occupation remains in full swing. Much is uncertain, but this much is clear: In an era of pervasive digital networks that instantly deliver news with scant human help, the successful journalist will be, above all, a knowledge maker.”

In conclusion, I want to agree with the school of thought that in this current situation of Disruptive Innovation, where editorial authority seems to not be solely in the hands of Journalists and editors who were referred to as Gatekeepers of news, Journalists have become more like verifiers or authenticators of news.