By: Roderick Matthew.

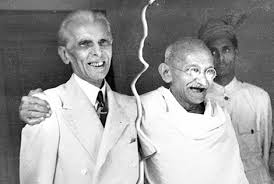

The modern history of South Asia is shaped by the personalities of its two most prominent politicians and ideologues – Mohammad Ali Jinnah and Mahatma Gandhi.

Jinnah shaped the final settlement by consistently demanding Pakistan, and Gandhi defined the largely non-violent nature of the campaign. Each made their contribution by taking over and refashioning a national political party, which they came to personify. Theirs would seem, therefore, to be a story of success, yet for each of them, the story ended in a kind of failure.

How did two educated barristers who saw themselves as heralds of a newly independent country come to find themselves on opposite ends of the political spectrum? How did Jinnah, who started out a secular liberal, end up a Muslim nationalist? How did a God-fearing moralist and social reformer like Gandhi become a national political leader? And how did their fundamental divergences lead to the birth of two new countries that have shaped the political history of the subcontinent?

According to Roderick Matthews “There are two different

distinct types of political leaders: those that acquire a

position by outlining a vision, which attract mass support,

and those that acquire office and then become a mouthpiece

for sectional interest. Gandhi was of the first type,

bringing something distinct and original into Indian

Politics as if from nowhere .Jinnah was of the second type ,emerging out of the Muslim community as

the one man who could speak for them at a national level.”

of the second type ,emerging out of the Muslim community as

the one man who could speak for them at a national level.”

A work of stunning superficiality by a well-meaning person, Jinnah vs. Gandhi by Roderick Matthews is based neither on any original research nor does it provide any new insights. The flow of opinion is unremitting; generalisations and hackneyed clichés abound. So do contradictions and factual errors.

The book suffers by comparison with two other works on the same subject, Jinnah and Gandhi: Their Role in India’s Quest for Freedom by S. K. Majumdar and Gandhi vs Jinnah: The Debate over the Partition of India by Allen Hayes Merriam. Matthews also ignores H. M. Seervai’s Partition of India: Legend and Reality and B. R. Ambedkar’s work of seminal importance Pakistan or the Partition of India.

Jinnah vs. Gandhi is not a hatchet job on Mohammed Ali Jinnah but rather a canonisation of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, an “ascetic, moral reformer and political maverick,” which does injustice to his skills as a politician. Factual errors in the book reflect the shoddy approach on matters big and small. The two did not meet “for the last time on May 5, 1947 at Jinnah’s house in Delhi” as stated, but in the viceroy’s house under the auspices of Lord Mountbatten. Withouting citing sources, the book says, “Motilal was correct that Jinnah, circa 1929, could safely be ignored … he was only one voice among many.” When Jinnah was abroad in 1928, Motilal Nehru told Purshottamdas Thakurdas “I can think of no other responsible Muslim to take his place.” When he returned, Nehru remarked “So much depends on Jinnah that I have a mind to go to Bombay to receive him.”

Matthews writes that “Gandhi always defined himself by his opposition to colonialism while Jinnah was defined primarily by his opposition to Gandhi.” Only a crass ignoramus would write thus. Overruling his colleague M. R. Jayakar’s strong objection, Jinnah as president of the Home Rule League in Bombay admitted Gandhi as a member on the condition that he accepts its objectives. Gandhi flouted it by a coup and Jinnah resigned; not alone as Matthews suggests but with 18 others.

Jinnah “began his career thinking within an ‘Indian’ framework, in the sense of nationalist opposition to British rule” we are told early on in the book, which is very true, indeed. But three pages later we are told that “Jinnah can be understood as a Muslim community leader from the very start of his political career.” And then, “starting his political career as a convinced Indian nationalist [Jinnah was] garlanded by Hindus and Parsis within the Congress for his lack of sectarian feeling.” At another point it is said that “the Aga Khan led the Muslim Delegation (at the RTC), but it was Jinna

For one who studied at Balliol, Mathews’ treatment of sources is cavalier, citing compilations rather than primary sources. Superlative confidence provides company to egregious incompetence. He soars high in the clouds of his opinions and is disoriented on descent. Facts seem to confuse him.h who made the running” only to be followed a little later by “the Muslim leadership at the Conference came from the Aga Khan and Fazl-i-Husain, and Jinnah exercised little influence on them.”

Gandhi “expected truth to be the driver of beneficial change — his concept of truth included ‘love’ and ‘God’, and the motivation he wished to awaken was never a narrow or selfish thing,” we are told. On Khilafat, Gandhi “wanted to find a plainly moral issue upon which to unite the Hindu and Muslim communities, and he took (or mistook) himself as the standard of measurement of religious emotion and moral outrage.” Gandhi’s espousal of the Khilafat cause is accepted by most as an opportunistic move. Not only he did not help Bhagat Singh but he also gave Viceroy Lord Irwin a clear impression that he was not in earnest about helping him. His record at the Round Table Conference was dismal. In a statement on December 6, 1933, Iqbal disclosed that Gandhi had asked Muslims not to “support the special claims of Untouchables, particularly their claim to special representation”. On April 24, 1943 Jinnah made the same disclosure. In 1946 Ambedkar published the damning document itself.

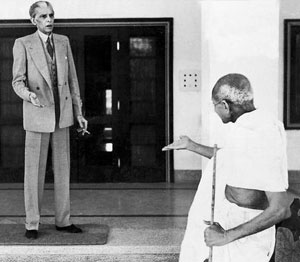

Any study on the contest between the two titans must ask precisely when and why they fell apart. Jinnah opposed Gandhi’s programme of civil disobedience at the Nagpur session of the Congress in December 1920 but praised him publicly. On December 3, 1929 he wrote to Lord Irwin, the Viceroy: “I left with the impression that Mr Gandhi himself is reasonable.” In 1937 the Congress refused to form a coalition with the Muslim League. When Jinnah proposed a meeting, Gandhi’s reply on February 24, 1938 was rude — meet Maulana Azad “in the first instance.”

Rebuffed, Jinnah propounded the Two Nation Theory and the

demand for Pakistan. The author tirelessly recalls events in

the subcontinent following Partition to justify his views on

politics before it. His critique of the theory is sound.

“Ultimately, for all its quirks, the Two Nation Theory

turned out to be more of a self-fulfilling prophecy than an

intellectually compelling idea. It held a deep attraction

for enough of its intended audience to ensure that once it

became familiar it acquired a force beyond intellectual

persuasion. It also gradually lost correspondence with

objective reality, and though undoubtedly convincing (and

useful) in the short term, in the longer view it was proved

conclusively wrong. Jinnah was compelled to insist that the

Muslims of India possessed a single real identity, but he

was mistaken.

Pakistan has been ravaged by divisions, and the release

from Hindu domination did not unearth a primal unity long

buried by minority status.”

Pakistan has been ravaged by divisions, and the release

from Hindu domination did not unearth a primal unity long

buried by minority status.”

But the main cause of the rift eludes Mathews: “The question is often asked how the main advocate of Pakistan — Jinnah — could ever have taken up such a cause after starting his political career as a convinced Indian nationalist, garlanded by Hindus and Parsis within the Congress for his lack of sectarian feeling. This question can be answered all through the narrative of Jinnah’s life in small steps. There was no abrupt break, turning point or conversion … It was his trust in the good faith of Hindus at large that failed him.”

Only a person utterly ignorant of Jinnah’s outlook would write this. Jinnah did not lose “his trust in the good faith of Hindus at large” but in that of Gandhi, Patel and others. Why is it that a man who got along famously with Tilak, Gokhale, Malaviya, Lajpat Rai and K. M. Munshi found Gandhi a difficult customer to deal with? For three reasons. From the very beginning Gandhi acted as mentor to all and became the sole leader. He was impervious to reason and had no time for safeguards for Muslims. In 1947, he demanded for the Hindus veto rights in a United Bengal which he would never concede to Muslims in a United India. It was Gandhi who torpedoed the Cabinet Mission’s Plan in 1946. Nehru only followed him. When Maulana Azad proposed a flexible federation Gandhi replied on August 16, 1945, “I do not infer from your letter that you are writing about my Hindus. Whatever you have in your heart has not appeared in your writing” (Transfer of Power, Vol. 6, p. 172). On July 24, 1947 Gandhi wrote to Nehru opposing Azad’s membership of independent India’s first Cabinet: Gandhi brooked no dissent. Jinnah would submit to no autocrat. At the end, Matthews picks holes in books on Jinnah with amusing results. His own book is entitled to a distinction all its own. It is the worst book on the subject written outside South Asia.