It ain’t easy being black in America.

A simple glance at the data will tell you why. Let’s start with education. According to the National Centre for Education Statistics, high school graduation rates for blacks stand at 68% compared to 85% of their white counterparts. The drop-out rate among African-Americans is twice that of white students.

Meanwhile, while the gap when it comes to college enrollment has narrowed over the last few years, graduation rates still show a discrepancy. Ben Casselman of FiveThirtyEight points out that:

Of students who entered college in 2005, [according to] the most recent data available, 62 percent of whites got a degree within six years, versus 40 percent of blacks.

When it comes to jobs, over at the Pew Research Centre, Drew Desilver reveals that for the past 60 years, the rate of unemployment amongst blacks has, on average, been twice that of whites. Research suggests that African-Americans tend to be “the last to be hired in a good economy, and when there’s a downturn, they’re the first to be released.”

On matters of law and order, black men “were more than six times as likely as white men to be incarcerated in federal and state prisons.” Blacks have the highest poverty levels of all racial groups in America with 15 million more living without health insurance compared to whites. Children born to black women are “1.5 to 3 times more likely to die than those born to women of other races/ethnicities.” According to the 2013 Census, homeownership for blacks stood at 43.2%, barely changed from the 1970s rate of 41.6%.

Now, all this is not to suggest that thing have not improved for blacks in America.

Political participation among African-Americans has increased substantially since 1965, when the Voting Rights Act was passed banning racial discrimination in voting. Apart from having the highest office in the land occupied by a black man, President Barack Obama is among 10,500 elected African-American officials, according to data compiled by the Joint Centre for Political and Economic Studies. This figure compares to just under 1,500 in 1970. Efforts to restrict voting in some states not withstanding, in the 2012 presidential election, for the first time in the history of the US, a higher percentage of black voters showed up at the polls compared to whites.

And as Juliet Eilperin points out, despite the challenges that still persist in education, some progress has been made:

In 1964, 25.7 percent of blacks age 25 and over had completed at least four years of high school; that percentage stood at 85 percent last year. During that same period the number of blacks with a high school diploma rose from 2.4 million to 20.3 million. Between 1964 and 2012 the percentage of blacks age 25 and over who completed at least four years of college increased from 3.9 percent to 21.2 percent, with the number of blacks boasting at least a bachelor’s degree rising from 365,000 to 5.1 million.

Poverty levels, too, have declined. Here is Ms. Eilperin again:

Back in 1966 the poverty rate for all races in the United States was 14.7 percent, but it was 41.8 percent for African Americans. Two years ago the poverty rate for African Americans was 27.6 percent, according to the Census.

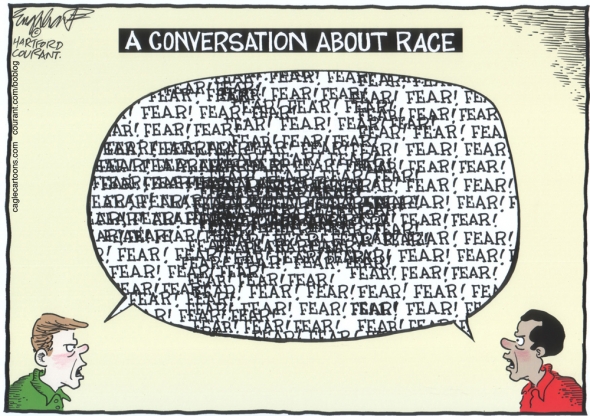

Nevertheless, based on almost any measurement, African-Americans still lag far behind their white counterparts in social and economic advancement. While there is almost universal consensus on this point, what has been more difficult to agree on is why this is the case. Is it because of racism? Or are there other factors at play? To answer these questions, Americans need to honestly confront the issue of race and as a nation figure out where the problem lies.

—

On the afternoon of August 9th, an 18 year-old young man by the name of Michael Brown, was walking down the street with a friend of his in Ferguson, Missouri, when he got embroiled in an altercation with Darren Wilson, a police officer, that led to him being shot at least six times and killed. The nature of their confrontation still remains in dispute (it should be noted, however, that a recent video obtained by CNN shows witnesses say that Mr. Brown had his hands up at some point during the altercation before he was shot.) What is clear however is that Mr. Brown was unarmed and happens to be black, while officer Wilson is white.

Did the racial identity of Mr. Brown contribute to his killing?

I, personally, do not know what Officer Wilson was thinking when he shot at an unarmed young man six times. But the response by the black community of Ferguson points to a belief that Michael Brown’s blackness was at the centre of why he was killed. According to The New York Times, during a recent vigil for Mr. Brown, angry shouts of “we are tired of this racist police department” were heard.

These feelings have not emerged out of a vacuum.

Over two thirds of Ferguson’s residents are black. Yet only 3 oFerguson Police Department’s 53 officers are black. The town’s Mayor is white, and so is its 6 City Council members. Furthermore, a recent study by ArchCity Defenders, a Saint Louis-based legal aid firm, discovered that in Ferguson there was significant disparities in the way that the police treated black residents. The report, as quoted by Peter Coy in a Bloomberg Businessweek article, found that:

86 percent of vehicle stops involve a black motorist, even though blacks make up only two-thirds of the population. After being stopped, blacks are twice as likely to be searched, even though searches of blacks discover contraband only two-thirds as often as searches of whites.

It seems to me, for black folks in Ferguson, the death of Michael Brown is a tragic emblem of years of racial discrimination. What followed – the protests, riots, looting – was their way of saying, ‘something needs to change.’

—

The election of the first black President in Barack Obama gave some hope that the US was about to enter a “post-racial” phase. But, six years into the Obama era, it seems like America’s racial divide has barely abated. As The New York Times put it:

Across a broad range of economic and demographic indicators, the data paint a largely depressing picture. Five decades past the era of legal segregation, a chasm remains between black and white Americans – and in some important respects it’s as wide as ever.

In fact, some have argued that the deep opposition that Mr. Obama himself has experienced during his time in office is racially motivated. Former President Jimmy Carter has been quoted as saying, “I think an overwhelming portion of the intensely demonstrated animosity toward President Barack Obama is based on the fact that he is a black man, that he’s African American.”

Whether that is the case or not, Mr. Obama himself has struggled to talk about race since he got elected. Remember the “beer summit”, the awkward gathering between Mr. Obama, a Cambridge, Mass., police officer and an African-American academic, following the President’s remarks that the white police officer had “acted stupidly” after he arrested the black Harvard Professor Henry Lois Gates as he was trying to get into his house? Or last year, when he addressed the not guilty verdict in the Trayvon Martin case, the Florida teenager who was shot and killed by a neighborhood watch coordinator, and found himself criticized for “politicizing” the issue. President Obama’s difficulty in engaging the country in a conversation on race reflects the larger challenges Americans face on the issue.

The reaction to the situation in Ferguson is a case in point. According to a New York Times/CBS poll, 57% of blacks think that Brown’s shooting was “not justified,” with only 18 percent of white respondents agreeing.

If the country can’t agree as to why racial disparities exist, it is difficult to see how it can solve some of the challenges associated with it.

However, the answer may lie in a recent study by the Public Religion Research Institute, that examined Americans’ social networks. Here is what they found:

Fully three-quarters (75 percent) of white Americans report that the network of people with whom they discuss important matters is entirely white, with no minority presence, while 15 percent report having a more racially mixed social network. Approximately two-thirds (65 percent) of black Americans report having a social network that is composed entirely of people who are also black.

That is an extraordinary revelation and shows the depth of the challenge the US faces. To solve the problem of race in this country, Americans are going to have start to engage with each other, openly and honestly, about this issue. Otherwise, black and white America will continue to live in alternate realities to the detriment of the future cohesion of the nation. And for some, that realization has started to sink in. As one white resident of Ferguson put it:

‘“We interact together, we have a good time together, we integrate, but we never talk about these things,” he said. “I think the perspective of a lot of white people is not really thinking that these feelings are sitting out there. And maybe in the black community they’re not only thinking about them, they’re wondering why we’re not talking about them.”’

(Cartoon by Bob Englehart, Cagle Cartoons, The Hartford Courant)

Ndugu Omar, that your write-up required loads of reading isn’t in doubt. Thanks for delivering.

Omar,

This is a great and informative post! You included detailed information and I like that you included a lot of data. As the statistics show, improvements have been made, such as with poverty levels and education. But racism is still a huge issue that needs to be dealt with in our country. I don’t think it will be easy and it will take a lot of time but as you said, Americans must be open and honest about the issues in order to continue to see improvement.

Hard work on this piece, Omar! Good structure, lots of info. Thank you for that!