Before I read my book, Drive, by Daniel Pink, I had seen a Ted Talk of his online that fascinated me. In his talk he makes pretty bold statements about how everything businesses are doing contradicts the science on motivation research. It’s a pretty grand claim, and I couldn’t help wondering if I was partially believing him because he was very charismatic and clearly knew how to structure an argument (he does mention going to law school).

Before I read my book, Drive, by Daniel Pink, I had seen a Ted Talk of his online that fascinated me. In his talk he makes pretty bold statements about how everything businesses are doing contradicts the science on motivation research. It’s a pretty grand claim, and I couldn’t help wondering if I was partially believing him because he was very charismatic and clearly knew how to structure an argument (he does mention going to law school).

When I got into Pink’s book, I noticed that his confidence really carries over into his writing. Every point he presents seems flawless in its logic and the book was truly compelling.

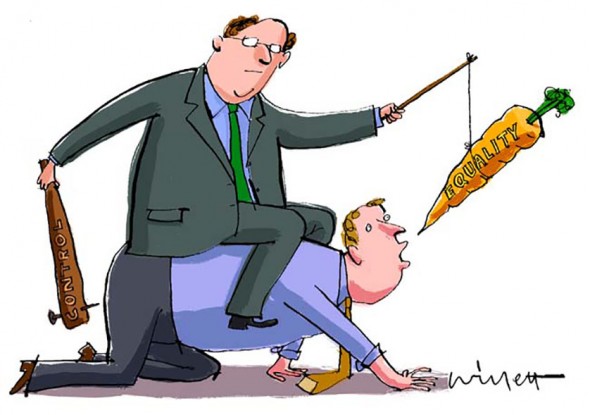

I was pretty entranced by Pink’s words, but when I finished the book I forced myself to take a step back and objectively look at it. From how much Pink dumps on companies that try to motivate their employees extrinsically (bonuses, pay raises, etc) he really neglects to interview any. There’s no way that the majority of companies are parading around knowing nothing about intrinsic motivation. But maybe it’s just the only thing that they can justify using? I really would’ve liked to have heard from companies that do use extrinsic motivation strategies and stillstand by them. I thought that was a key part missing from the book.

My faith in Pink shaken, I took to the Internet to see if anyone else shared my frustration. One of the blog posts I read, by Dr. Fiona McQuarri, mentions that she “was motivated (so to speak) to read this book because I teach about motivation in some of my classes, and some of my research deals with it as well.”

McQuarri’s post, “DANIEL PINK’S ‘DRIVE’: A SHORT JOURNEY ON A TINY PIECE OF ROAD,” mentioned several researchers and experiments that Drive somewhat conveniently leaves out. McQuarri cites 4 major theories that Pink never mentions.

Frederick Herzberg’s motivation-hygiene theory (also known as the two-factor theory). While this theory hasn’t been strongly supported by research, it makes the important point that if workers are dissatisfied with basic things in their workplace – like working conditions, salary, and job security – then it will be difficult to motivate them with any kind of reward.

Clayton Alderfer’s ERG theory. This theory builds on the work of Abraham Maslow by suggesting that workers are motivated by the desire to fulfill their perceived needs, and that some needs will only become relevant once others needs are fulfilled. In other words, there is a hierarchy of needs, and what motivates a worker at any given time will depend where they are located on that hierarchy. (Amazingly, despite the huge influence of Maslow’s work on motivation theory and research, and how widely Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is taught, Maslow gets only one short mention in Drive.)

Douglas McClelland’s achievement motivation theory (or ‘needs theory’) This theory suggests that workers are motivated by their perceived needs to achieve, to gain power, and to feel affiliated with others. McClelland proposes that these needs are not instinctive, but are instead acquired or learned through experience, which is particularly important in understanding the actions of adult workers in the context of a workplace. Workers’ motivations may change as they acquire these needs, or have more experience with them.

Victor Vroom’s expectancy theory. This theory suggests that if workers are going to be motivated to achieve a certain level of performance associated with an outcome, the workers need to believe that their effort will translate into performance; that their performance will result in an outcome; and that the reward associated with the outcome is valuable enough to them to justify their effort.

As I read through the experiments that Pink left out, I realized that businesses really can’t be as behind as Pink makes them out to be. I also thought it was a little slimy of him to leave out all these theorists that clearly made big contributions in the science of motivation. As McQuarri puts it, “Drive‘s subtitle promises “the surprising truth”, but almost all of what Drive has to say is no surprise, because it’s been said already, and not all of it is true either. “

So, all in all, I thought that Drive was beautifully written. It really did make me think and question everything I thought I knew about motivation. But after doing my research on it afterwards, I am pretty disenchanted now I know how much he left out.

I do think this would be a useful book for managers that are rewarding work that would not respond well to the “carrot and stick” method. As Diane Danielson puts it in her online book review, “Highly recommend for anyone managing creative types.”