Aung San Suu Kyi is a product of incredible privilege. Her father Aung San, was a revered liberation leader who fought for his country’s independence. Meanwhile, Suu Kyi’s mother enjoyed a distinguished career as a diplomat. It almost seems inevitable that, she herself, was going to go into politics.

She went to college in India where she spent time with the Gandhis. She then proceeded to get her undergraduate degree at Oxford University. While there where she was introduced to Michael Aris, the man who would later become her husband, by Lord Gore-Booth, the paragon of the British establishment and great-grandson of the Arctic explorer Sir Henry Gore-Booth. They had two children, both boys, Alexander and Kim.

But she left these privileges and decided to go back home. Already, we start to see the idea of sacrifice emerging as a central aspect of her leadership style. “If they required the help of people outside Burma we would have to go back,” she once said.

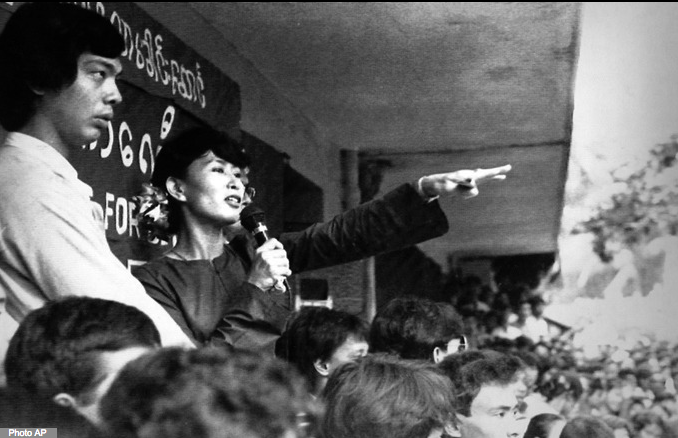

So in 1988, while at home visiting her sick mother, Aung San Suu Kyi found herself in the middle of the so-called “8888” protests that drew over a million people in the middle of Rangoon, Burma’s capital city. She gave her first political speech during the protests and from then on became at the forefront of Burma’s opposition movement against the country’s military dictatorship. She formed the National League for Democracy (NLD) with the help of some disillusioned generals and began traveling the country to advocate for democratic governance. While at first people would come to see her mainly because of the memory of her father, it became clear that she was her own woman. One aide says:

“At the very instant I saw her, I knew ‘She is my leader.’ We admired General Aung San so much, so it was no problem for us to follow her. But she herself proved to be a very courageous, very strong-willed person.”

So we see another aspect of her leadership style manifest itself here. Her ability to connect with others at a deeper and visceral level and inspire them to great change.

Soon after, she was arrested by the military junta, who placed her under house arrest. She spent 15 of the next 21 years in and out of house arrest. In 1997, her husband was diagnosed with terminal cancer and the junta would not grant him a visa to visit with his wife. She never went to see him for fear that her return would be blocked by the dictatorship.

Michael Aris died in 1999 and he never got a chance to say goodbye to his wife.

Again, we see that concept of sacrifice come to the fore again for what she believes is the greater good: An independent and democratic Burma.

In fact, her eldest son has reportedly been vocal about his dissatisfaction with her mother’s decision to prioritise politics over their family.

Her brother, meanwhile, is close to the regime and sued her for the rights to their family estate. Yet, she has shown remarkable fortitude to overcome these “family ruptures.” This is another important characteristic of her style. A friend of hers has said:

“I strongly believe that she has no bitterness…She has never shown anger or short-temperedness. It is a quality of indifference that I have only come across in senior Buddhist monks…Inside the heart you may have some feeling, but your mind is above the heart. . . She loved her sons very much, but you may say that her Buddhism transcended it.”

That ability to transcend the troubles of the present and focus on the vision of freedom for her people has made her an icon and a symbol for democratic movements across the globe, wherever the fight for human rights is happening.

In November 2010, Aung San Suu Kyi was released from prison. In April 2011 she pivoted from the unwavering principled leader she had been for close to three decades to a politician. She made the pragmatic decision to meet with President President Thein Sein and endorsed the latter’s reform agenda, which paved the way for her and her party the NLD to run for elections in 2012. She won a seat in parliament and is running for President in the 2015 general election.

Her new, pragmatic posture, however, has not gone without criticism. As Reuters put it:

“Ethnic groups accuse her of condoning human-rights abuses by failing to speak out on behalf of long-suffering peoples in Myanmar’s restive border states. Economists worry that her bleak public appraisals of Myanmar’s business climate will scare foreign investors. Political analysts say her party has few real policies beyond the statements of its world-famous chairperson. She must also contend with conflict within the fractious democracy movement she helped found.”

In response to her critics, she has said:

“I don’t like to be referred to as an icon, because from my point of view, icons just sit there. I have always seen myself as a politician. What do they think I have been doing for the past 24 years?”

But by being careful in her political approach, she has been able to win an election and give her a chance to put herself in a position to win power in 2015. Three years ago, this would not have been conceivable. Now, it is a real possibility. The question then is: is an uncompromising stance the best way to lead a movement for change or is pragmatism the more suitable option to achieve results. Aung San Suu Kyi is learning to figure out the difference.

Amélia Goe, Amanda Ames and Lila Diva Ojha contributed research.

Hi Omar, Amelia, Amanda and Lila!

I really appreciated your presentation and post because they allowed me to learn so much about Aung San Suu Kyi, who existed mainly as an idol in my mind. Her sacrifice and commitment astound me! I don’t think I’d be capable of sticking to a personal cause like she did.

Thanks for the presentation!

Hi Friends,

I have heard once about 8888 protests. From your blog I found out a lot of inspiring moments, The best one is that a leader can be born and act even in the most slowly developed country, like Burma is. you managed to create her character within this blog. Thank you