By Omar Mohammed, Amelia Goe, Amanda Ames and Lila Devi Ojha

What do you do when you come into work one day and discover that one of your employees has perpetrated the biggest fraud in the history of your company?

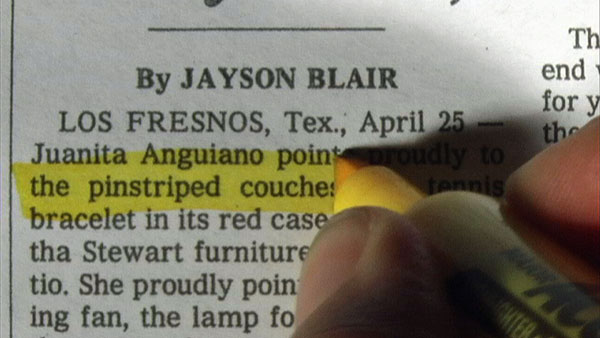

This is the question that confronted The New York Times in the spring of 2003. A reporter working for The San Antonio Express-News noticed some similarities between a story she had published with one that appeared in the paper of record on April 26th, 2003. Ms. Macarena Hernandez, the reporter, knew the journalist who may have plagiarized her work. It was her former co-intern at the Times, Jayson Blair. She told Vanity Fair, “it was just completely obvious that he had taken major chunks of [my story].”

Ms. Hernandez got in touch with the Times and it quickly became clear that they had a problem. As per Vanity Fair again:

[Managing Editor Gerald] Boyd immediately summoned national editor Jim Roberts. Jayson Blair—a seemingly indefatigable 27-year-old reporter—had been working for Roberts for the last six months, ever since he had been drafted as an extra set of legs to cover the Washington, D.C.– sniper story, in October 2002. Boyd, Roberts, [Recruiter Sheila] Rule, and Bill Schmidt, an editor in charge of newsroom administration, met in the managing editor’s office. It was a dispiriting meeting. “By the time I got there, they had already concluded this looked really bad,” says Roberts.

Ultimately, Roberts confronted Blair who, a few attempts protesting his innocence aside, resigned soon after.

The Times Executive Editor Howell Raines realized the seriousness of the issue. “When you’re wrong in this profession, there is only one thing to do: And that is get right as fast as you can,” he said. He added: “The solution to bad reporting was good reporting.”

A team of reporters were assigned the task of examining Jayson Blair’s career at the Times, in effect re-reporting his stories. This took the form of an awkward exercise whereby Times reporters found themselves investigating their own newspaper. Internally, the process was dubbed “The Blair Witch Project,” after the horror film. Eventually, the investigation revealed that of the 73 stories Blair had written between October 2002 and May 2003, at least 36 had substantial problems. “To the best of my knowledge, there has never been anything like this at The New York Times” Alex S. Jones, a former reporter at the paper said to Vanity Fair.

So why did it happen? Well, the report produced by the Times, which appeared on page A1 of the newspaper on 11th May, came to this conclusion:

The investigation suggests several reasons Mr. Blair’s deceits went undetected for so long: a failure of communication among senior editors; few complaints from the subjects of his articles; his savviness and his ingenious ways of covering his tracks. Most of all, no one saw his carelessness as a sign that he was capable of systematic fraud.

“It’s a huge black eye” and “an abrogation of the trust between the newspaper and its readers,” said Arthur Sulzberger, Jr. Chairman and Publisher. “The New York Times…You would expect more out of that,” Glenda Nelson, a woman quoted in one of Blair’s stories who was in fact never interviewed by him, said.

Following the publication of the report, the positions of Mr. Boyd and his boss Howell Raines became untenable. Besides winning several pulitzer prizes, he had little allies within the newsroom. From The Wall Street Journal:

Under Mr. Raines, the autocracy become tighter and harsher, causing resentment to build among large portions of the staff. During an extraordinary mass meeting of Times staff…in a rented Broadway theater to discuss the Jayson Blair scandal, Mr. Raines conceded that his management was viewed poorly and promised to change. “You view me as inaccessible and arrogant,” Mr. Raines said, according to a Times account. “You believe the newsroom is too hierarchical, that my ideas get acted on and others get ignored. I heard that you were convinced there’s a star system that singles out my favorites for elevation. … Fear is a problem to such extent, I was told, that editors are scared to bring me bad news.”

By early June, however, Mr. Raines and Mr. Boyd were forced to resign, their dismissal “a result as much of their imperious leadership as of Blair’s bizarre deceit.”

Was Mr. Blair’s race, (he is African American) a factor in his time at the newspaper? It is difficult to prove a causal link, however he was repeatedly given the benefit of the doubt, first because folks did not believe that his erroneous stories were deliberate. Nevertheless, senior editors were also keen to encourage more diversity in the newsroom. From the Times report:

Mr. Blair’s Times supervisors and Maryland professors emphasize that he earned an internship at The Times because of glowing recommendations and a remarkable work history, not because he is black. The Times offered him a slot in an internship program that was then being used in large part to help the paper diversify its newsroom.

Ultimately, this was a case of an individual who took the faith and trust placed on him by his employer and spat on it. And in the process, causing one of the biggest scandals in the history of newspaper journalism.

Further reading:

– “Times Reporter Who Resigned Leaves Long Trail of Deception,” New York Times http://nyti.ms/1uKP7kB

– “Scandal of Record,” Vanity Fair http://vnty.fr/11Lef13

– “Troubled Times,” New York Magazine http://nym.ag/11Leycq

– “Page One: Inside the New York Times,” A documentary by Andrew Rossi

– “So Jayson Blair Could Live, The Journalist Had to Die” New York Observer http://bit.ly/11LfMEp

One Comment on “The Jayson Blair Affair”

Comments are closed.

You might also want to watch the film that is featured in the first image in this blog post. It’s called

“A Fragile Trust: Plagiarism, Power, and Jayson Blair at the New York Times” and is the first and only feature documentary to tell the whole story of the scandal. A Fragile Trust includes exclusive interviews from everyone involved in the scandal, including Jayson Blair and Howell Raines.