By Andrew Romanov

The United States of American and the Confederate States of America—the American Civil War pitted the two against each other in a violent war of “North” against “South.” Each side was very different from the other. Although the Union had a deeper treasury, the Confederacy had perhaps more talent on the battlefield.

As I perhaps foolishly describe my own leadership style as “participatory consultative authority”—and after having read Sun Tzu’s “The Art of War” (I’m on a military streak, I suppose)—it might be best to use the Civil War as an example in describing leadership tactics I admire in then-President Abraham Lincoln.

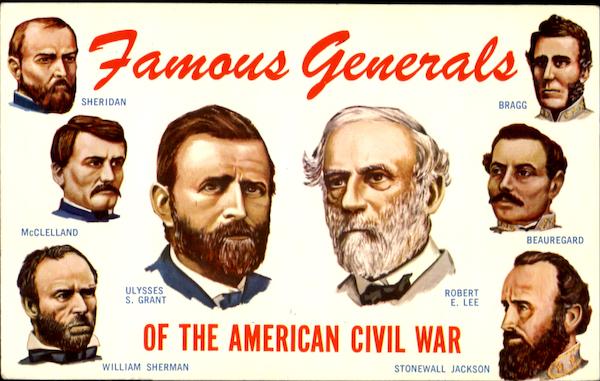

The Confederacy had one primary general—Robert E. Lee. A shrewd tactician and battlefield commander, Lee was supported throughout the war by Confederate authorities.

The Union, on the other hand, did not have such an easy choice. The first Commanding General of the United States Army, Winfield Scott, was an elderly veteran of the War of 1812 and retired shortly after the war started.

His successor, George B. McClellan was initially greeted as a savior, having built the Army to a formidable force. But he refused to move the army, despite pressure from Lincoln.

McClellan was soon relieved of his position. Lincoln was so frustrated with his generals and the course of the war that he reportedly began soaking up military texts and regularly visiting with advisors to perhaps lead the army himself as commander-in-chief.

The next Commanding General of the United States Army, Henry W. Halleck fared slightly better, but was also removed less than two years after he took the position after succumbing to the political pressures of his position.

Finally, Ulysses S. Grant was appointed and was capable enough to deliver the final blows to the Confederacy. Lincoln, a lawyer by training with no military background, was never forced to command the army himself.

While his experience was one of frustration, I admire President Lincoln’s leadership throughout the Civil War in the leadership of his generals. He consulted advisors and trusted generals (who sometimes were not able to deliver); he used his authority to make tough decisions; he even took steps to directly participate himself.

Ultimately, Lincoln and the North won. Despite having an early shortage of talent, his team reached its goals. And that’s leadership.