By Brooke Stobbe

Reviewed by Lila Ojha

Upon the inception of the internet and online expression, the free-flow of journalistic information was revolutionized: free and safe.

However, this freedom has been compromised, even in the United States. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has issued the 2013 Risk List of countries jeopardized from their freedom of expression.

Most interestingly, the first country listened on the 2013 CPJ Risk List is cyberspace, justified by repeated accounts of governmental eavesdropping, surveillance and cyber attacks in countries across the globe.

Former NSA contractor Edward Snowden helped reveal massive surveillance as an international issue. Violations of digital privacy, hackers and other such cases help identify issues of violence, censorship, attacks, and other such indicators CPJ used qualify countries on their list.

The remaining countries are Egypt, Russia, Syria, Vietnam, Turkey, Bangladesh, Liberia, Ecuador and Zambia.

Four key issues surface in reading and better understanding the immense pressure journalists in these countries face: brutal violence, legislation to stifle free speech, disturbing detaining rates, and the rise and crackdown on bloggers.

Interestingly enough, these issues often relate back to the dissipation of news online. For example, absolute brutality against bloggers (the only independent reporters) in Vietnam and Bangladesh are exposed through their publications online or, cyberspace. The fear then incited from the government’s surveillance is on the online platform.

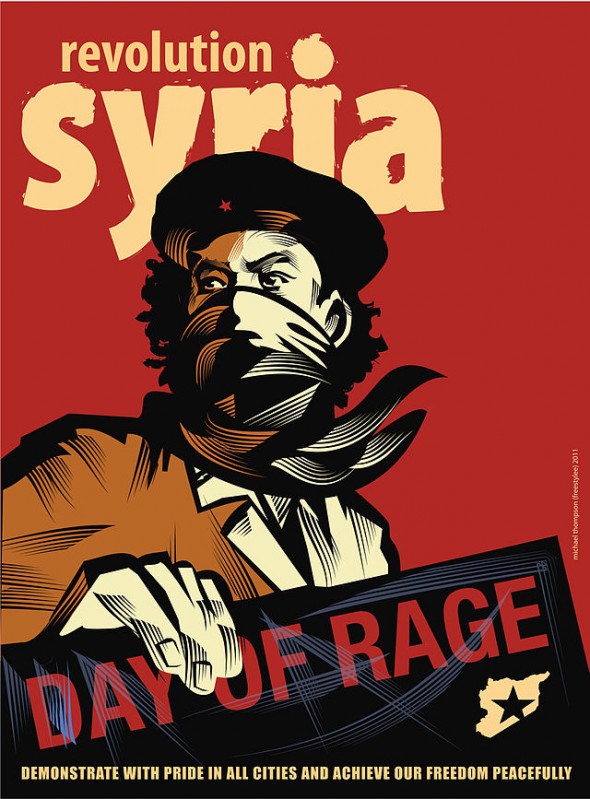

This kind of surveillance online, however, keeps stories from being told. Syria’s perilous conditions have worsened, keeping all international reporters out of the country. Even the President of Al Jazeera America Kate O’Brian said “I will not send someone to Syria… It’s just too dangerous.”

The intimidation factor is huge, with Zambia, Bangladesh, Liberia and others using criminal defamation laws to suppress publication. Egypt’s military regime and incarcerations, Vietnam’s containment, and Russia’s insistence on journalists registering as activists are just a few examples.

In Nigeria, the president’s chief secretary aide “referred to journalists as ‘terrorists,’” (pg. 214). In Turkey, journalists aren’t able to do journalism altogether “because the ones that have remained in media can’t really do proper reporting” (pg. 212).

How, then, do these fiercely opposed news organizations protect their journalists, sources, and integrity while still telling the stories, especially if the online platform now poses additional risks? When reporters can’t report, publishers are incarcerated, and citizens are silenced, the freedom to share information, across any platform, is choked, and human lives often suffer.

Brooke,

This is the true downside to a digital world. It’s easier, in most high-stake issues, for technology companies to cooperate with states than atrophy defending privacy rights of digital platform users.

Because of security concerns, many governments have a legitimate concern to know what’s being transmitted online, whether by journalists or not. It gets worse with data encryption by those who want to bypass state scrutiny.

States, however, often abuse this right rather to isolate and punish critics, not facilitate public debate. I attended an Internet Freedom training in Stockholm, and was mesmerized by how Sweden had what I have come to consider the most transparent approach to online free expression, defending and promoting this right including through co-sponsoring a UN resolution.