Reviewed by Brooke Stobbe

The concept of work-life balance has been defined as “prioritizing ‘work’ (career and ambition) and ‘lifestyle’ (health, pleasure, leisure, family and spiritual development/meditation).”

This definition, by default, assumes work to be formal employment where labor is rewarded with monetary payment for time-calibrated activity and deliverable.

In my country, Uganda, and outside of its formal western-modeled structure, work has a broader meaning and purpose, especially in rural societies. Time, in the context of my community, is more about activity: enabling a seamless transition from one to another.

That next activity is flexible and doesn’t have to be a pre-scheduled one.

Thus people don’t stress themselves with things such as ‘breakfast, lunch or dinner time’ to mean specific hours when to or not eat. In our villages, people do have a meal either when hungry or whenever food is available. Time is not a personal item; it’s what an individual does with it with or for the community.

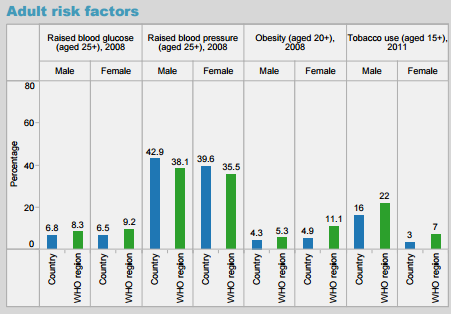

In Uganda’s towns, however, the cases of lifestyle diseases, known in medical circles as non-communicable diseases, is rising.

The World Health Organization says non-communicable diseases account for over 60 per cent of global deaths. “This burden is one of the major public health challenges facing all countries, regardless of their economic status,” the agency warns following startling findings in its 2010 survey. Part of the problem is poor eating habits and limited physical exercise.

Formal jobs keep employees for the most part seated for eight or more hours each work day, rendering them vulnerable to ‘lifestyle’ diseases caused by limited physical exercise. By contrast, in my home country, people plough the garden or weed with a hoe, or cut spear grass with sickle for thatching a house, meaning they vigorously exercise and work simultaneously.

As a child, I tethered goats and herded cattle at locations distant from home. The walk through nature’s inviting allure, playful interaction with other children, hunting and tree climbing, and fruit harvesting while in the wilderness was a combined work, leisure and pleasurable activity. This happens to date.

Women do laundry, weave baskets or table clothes as they cook or when waiting for customers in the market. Men cut through thickets to harvest and ferry poles for erecting building walls or make sisal ropes in the evening while teaching children family traditions and culture.

Thus it’s work, teaching/learning and leisure — all intertwined for a more holistic upbringing and productivity.

It’s the model of modern economics and power structures that impose the dilemma of work-life balance or remove that possibility. It’s not a universal application for all societies the world over.