Let me set the scene for you. Experts contend that this is the pre-eminent subject of our time. At the core of it is the very survival of the human race. The evidence behind it is overwhelming and those who have dedicated their lives to studying the issue say that this is real and as serious as it gets.

But not quite all of them, though. Some say that their colleagues are exaggerating the problem and have branded them “alarmist.”

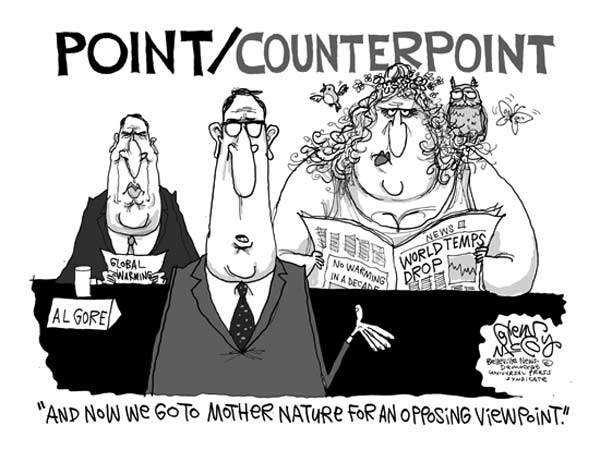

I am referring to here is climate change, global warming and the central question of what causes them. So as a journalist, confronted with with appears to be two competing arguments, what do you do?

At the core of what it means to be a reporter is to “be fair and balanced in presenting the contours of a debate.” Yes, an overwhelming majority of climate scientists believe that global warming is a real phenomenon and that it is caused by humans. In fact, a 2009 survey showed that 90% and 82% respectively believe in those conclusions. Does that therefore mean journalists should accept that a consensus has emerged and take as fact that global warming is indeed real? Aren’t we supposed to be objective in the way we cover stories and make sure that the minority view is also heard?

No, actually. A journalist’s commitment should be to the truth and not adhering to false equivalencies in the name of objectivity. Of course, the truth can be an elusive idea. However, attempting to establish the truth when covering a story should be the governing principle of any journalist. When it comes to climate change, media critics have chastised the mainstream press’ ambivalence on forcefully reporting the truth of the issue.

Robert S. Eshelman, writing in 2013 for Columbia Journalism Review (CJR), argues that journalists seem hypnotized by the complexity of the issue and as a result hide behind the cloak of reporting both sides of the story. He says:

“[I]t’s as if journalists are stuck in time, presenting the science as something still under debate. A notion to be evaluated, tossed around. As scientific certainty grows today’s reporters, editors, and producers should cease with the false conceit about a debate.”

Instead of balance, reporters should strive for accuracy, is Eshelman’s point. After all no journalist would give the argument that smoking cigarettes is not as unhealthy as it is claimed equal weight against scientists who have shown the opposite. So, why do journalists aspire to practice this concept of balance when it comes to climate change? Especially after an overwhelming majority of climate scientists have shown that climate change is real and caused by humans?

Part of the reason that journalists struggle with climate change may have something to do with the painful transition that the industry has endured over the last decade. With legacy revenue models decimated by the arrival of the internet, news organisations have been forced to reorient their priorities. Here is Eshelman again:

“When the media industry was flush with revenue, newsrooms were well stocked with experienced, issue-specific reporters and editors. But since the early 2000s, shrinking staffs, the elimination of environmental desks, and narrower news holes has made reporting on climate change even more difficult.”

Established outlets such as The New York Times, The Guardian and Reuters have seen their coverage of climate change deteriorate considerably. Alexis Sobel Fitts, also writing in CJR, points to a study that shows that in 2011, “The New York Times cut its global warming article count by 15 percent, and the Guardian slashed coverage by 21 percent that same year…Reuters, too, dropped its climate coverage by 27 percent.” While there may be some evidence that coverage has rebounded in 2013, social scientists suggest the shift is merely cosmetic. From Ms. Fitts:

Max Boykoff, who since 2000 has tracked climate coverage in the top five newspapers in the United States—The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, USA Today, the Los Angeles Times, and The Washington Post—found a drop in coverage in 2013. And Robert Brulle, a social scientist at Drexel University who monitors climate coverage on television news, said his preliminary data (measuring through the end of November 2013) found 30 stories, just a single story more than in 2012, which Brulle said was “statistically just a write off.

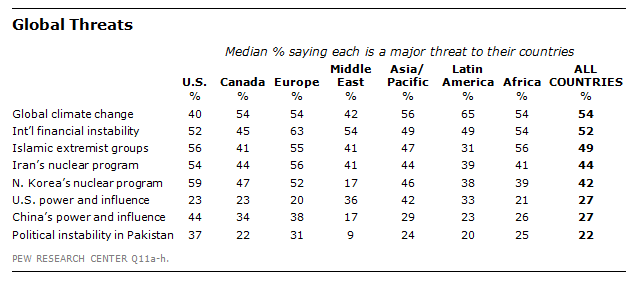

So what effect has this “ambivalent reporting” of climate change and global warming had on public opinion? Well, not particularly positive. To wit:

“According to a recent Gallup poll, only 24 percent of Americans surveyed saw climate change as an issue worth “a great deal” of concern. The issue was rated second-to-last in terms of importance, just before “race relations” on the survey. (Fifty-one percent responded that climate change was worthy of little to no worry.) And according to the most recent US National Climate Assessment, conducted in April, 64 percent of Americans surveyed believe global warming is happening, a rate that’s remained relatively steady since 2008.”

This begs the question: Have we then, as journalists, fulfilled our public service role when it comes to this issue? Are we communicating the urgency of what’s at stake? One reporter, who was asked about the issue, had this to say:

“My job is to tell readers what is happening in science, to provide facts, data, and context..I do not see my job as trying to influence readers’ views, just inform.”

Only time will tell if this will be enough.

(Cartoon via Pronk Palisades)

Reviewed by Travis Moore.

Omar,

You said, “A journalist’s commitment should be to the truth and not adhering to false equivalencies in the name of objectivity.” I disagree with this, because I think it insinuates that by mentioning these perhaps, “false equivalencies” the journalist is advocating for them. If a journalist is truly doing their job, they will be both balanced and accurate. Presenting both sides that exist is key in letting the reader decide what they believe. Journalists should not try to shape the reader’s belief. However, leaving out key concerns of others is not fair reporting and thus not fair for the reader.

That being said, you provided great resources on the matter and I enjoyed those thoroughly.