Somalis in Phoenix? Yes, you read that right.

I spent the last two and a half years inside this community; observing them, researching them, and most of all, interacting with them.

The Somali refugee population in Phoenix is between 15,000 and 20,000. Although these numbers are high, the Somalis are largely invisible to the greater Phoenix metro.

Last Thursday, I presented all my research, findings, and conclusions to my thesis team and some supportive audience members. My Honors Thesis Defense may now be over, but the research never will be. I plan to continue spreading awareness about the Somali community, volunteering with them, and learning more about them each day.

I would like to use this blog as a introduction to a key Somali refugee issue in Phoenix: education. As part of my thesis project, I produced a documentary entitled Speak, the story of two Somali children in Phoenix public schools. The hardships they face are unimaginable to most Americans.

The two students I followed, Hana and Fuad, are a great example of what most Somali students experience.

Hana is in 8th grade, Fuad in 7th. They have attended many different schools since coming to America in 2010 with their grandmother. Hana gets good grades and loves reading romance novels while Fuad gets mediocre grades and loves to goof off and play basketball. They both love YouTube and prefer to speak Somali and English at the same time, mixing random syllables of different languages together. They enjoy American pastimes, but in Hana’s case, all while wearing her hijab.

From the beginning, Phoenix schools did not know what to do with the influx of Somali students entering their district. They didn’t know what to do–so they really did nothing. The programs created in the 1970’s to integrate Spanish learners into classrooms was re-purposed to include Somali students, no matter that Somali and Spanish are not the same.

Teachers aren’t educated on their student’s new culture or previous life. Students are not taught basic American culture, like hand-raising and bathroom breaks, before entering the classroom. They are not even taught English. There is no intermediate period of learning English for Somali children when they come to America; they are immediately put in a classroom. Hana describes in Speak how for at least the first six months, she had no idea what her teacher was saying or doing, “I just sat there.” Fuad said, “I would just draw.”

Current laws in Arizona do not allow the use of a student’s primary language to help them learn their second language. Imagine learning another language in that other language.

Not only do laws need to be addressed in order to fix this issue, but so do attitudes. I hope spreading awareness about this community will make Phoenicians open their eyes and realize the Somalis are part of their city and they must be recognized as such.

One must not fear a different language.

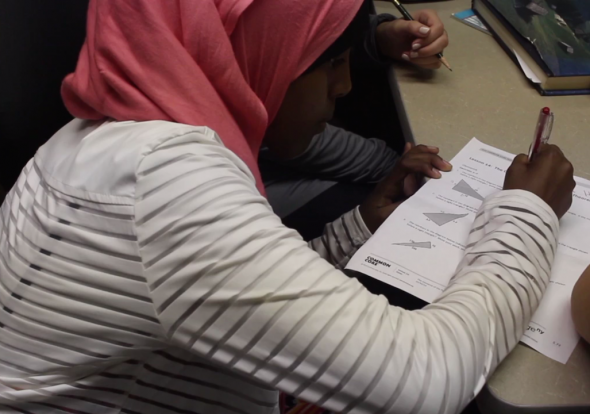

I feel adequately qualified to explain the Somali students’ hardships after the countless hours I have spent as a tutor at the Somali American United Council of Arizona. My first day tutoring I taught five sisters to divide. The family had just came to the United States three months before. The notes from their teacher to the parents were in English: “your daughter does not pass the standard for division. Please do her homework with her.”

Too bad their parents didn’t know how to read that note. Let alone divide.

I taught them division by using dots and circling rows and columns because we didn’t speak the same language. After three hours, when Sahra circled 7 dots to complete “28/4”, we finally spoke the same language. it was smiles, high fives, and hugs.

Human dignity and spirit can be a language, too.

Post by Bailey Netsch

Edited by Narmina Strishenet