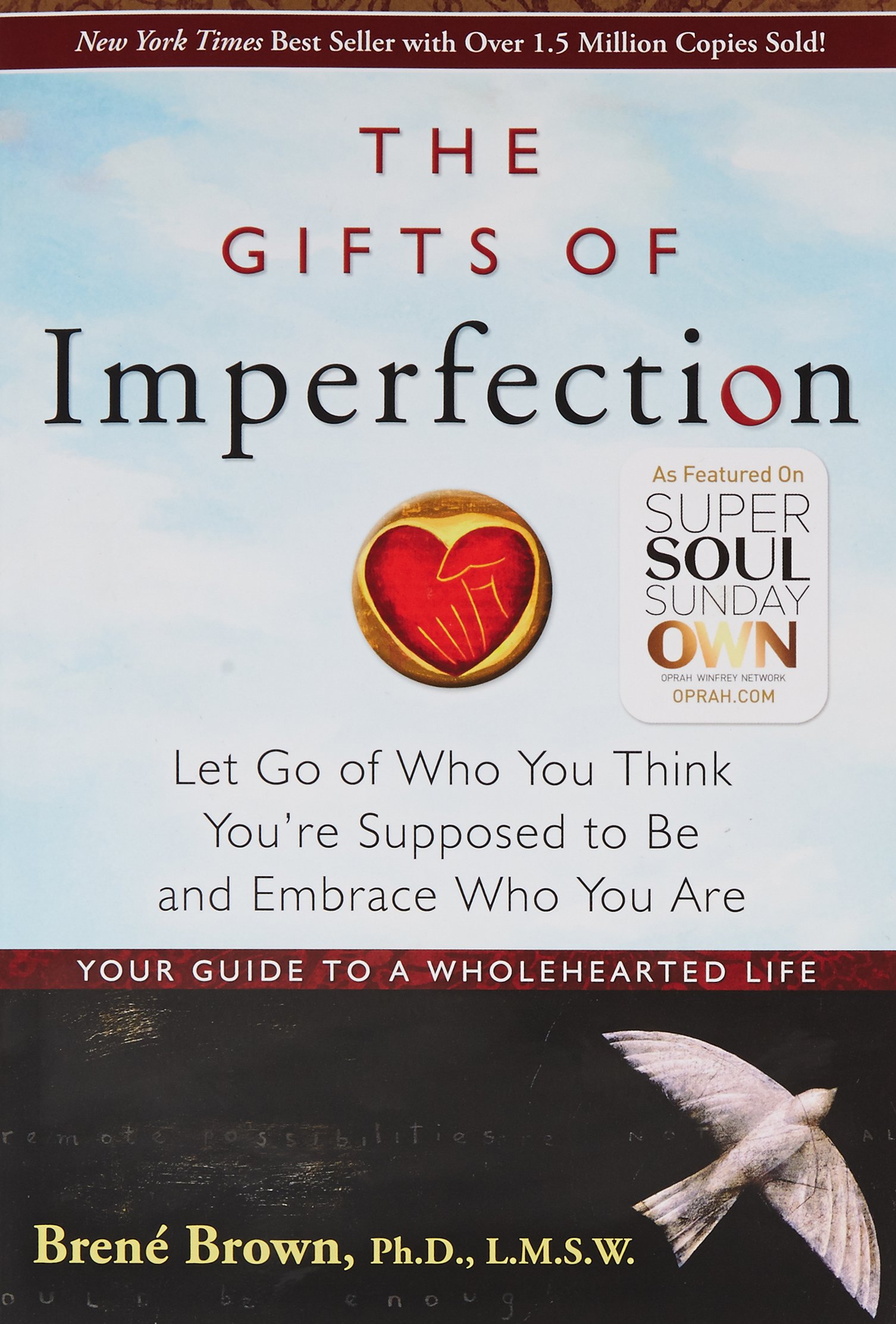

The Ethical Journalism Graphic

Journalism is the first rough draft of the history as stated by Philip Graham. The way we practice journalism, namely ethic code, imposes significant impacts on our society. However, things have changed a lot. Decent journalism and its ethical code are both undergoing a hard way.

From the Washington Post office

Avoid stereotyping that Impacts Reporting

Since last year, traditional journalism has been in danger of being overwhelmed by rogue politics and a communications revolution that accelerates the spread of lies, misinformation and dubious claims.

In such a time of change and challenge, an age of hope and fear, an epoch of belief and incredulity, journalism ethics are more important than ever. One of the widely accepted ethical code is the SPJ Code of Ethics(https://www.spj.org/ethicscode.asp). These ethical standards have given us guidelines for how to report in a more accurate, fair and honest way.

Among them, I think the most important one is that journalists should avoid stereotyping by examining the ways their values and experiences may shape their reporting.

When Reporters Get Personal

The reason why I chose this specific one is because it is an extremely important but easily neglected ethical code at any given time. The movie, The Year of Living Dangerously, truly strikes a chord with me by raising great concerns over this critical problem of what if the journalist is tendentious.

This movie is about a group of foreign correspondents in Indonesia on the eve of an attempted coup in 1965. Billy Kwan is a typical leftist journalist, who holds strong faith on revolution, in the 1960s when national liberation accompanied by communism uprising rapidly swept around the world. He is a strong supporter of the Sukarno regime, which allied with communism countries.

From the Year of Living Dangerously. Billy(left) and Hamilton (right)

Billy’s strong political inclinations inevitably affect the objectivity of his opinions over the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) and Sukarno regime. His friend Hamilton discovers the weapons shipment to Indonesia for arming the PKI. Hamilton decides to verify the story and cover the communism rebellion. However, Kwan strongly opposes it and withdraws his friendship from Hamilton, because he still believes Sukarno regime and revolution.

When I watched this scene, I was wondering how does Billy cover Sukarno the person he feels strong sympathy with? In his article, is Sukarno a nationalist leader or a dictator who attempts to manipulate both PKI and the conservative Muslim military regardless of people’s interests? What irony! In the end, Billy is killed when he expresses outrage to Sukarno the man he once strongly supports.

Are we the captive of the personal values and biases?

History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes as Mark Twain is often reputed to have said. Although Billy is a fictional figure, journalist’s personal bias and view is a real problem that still exist.

Margaret Sullivan, the fifth public editor appointed by The New York Times, said one of her reader commented on her blog by writing that “I think the instinct to maintain the old fiction that professional journalists can free themselves of their personal views and habits of mind is doomed to failure.”

In an increasingly polarized society, or the post-truth era, it is an increasingly important subject, and a complex one. On one hand, journalists from mainstream newsroom strongly feel them being unfairly challenged and smeared by biased populists and nationalists. On the other hand, do journalists also hold the personal bias against the audiences who have different opinions with them?

The bias on each side has widened the gap between journalism and their audiences. In China, we have the same problem. “Why is western media biased against China?” is a question posed to western journalists in China. Many Chinese audiences share the idea that western media outlets don’t cover China fairly by exaggerating its weaknesses and ignoring its successes.

Although I don’t have evidence if western journalists are biased against China, I wonder should western journalist integrate their personal value into their reporting for influencing the Chinese audiences who dislike the value of democracy and freedom? Or should they just deliver the middle-ground reporting that muddies the truth in the name of fairness for pleasing Chinese audiences?

It sounds like a to be or not to be dilemma. Opinions vary. Jay Rosen, a New York University journalism professor, believes that traditional notions about impartial reporting are fundamentally flawed. Instead, journalists should come out and tell readers more about their beliefs.

Conversely, Philip Corbett, New York Times’s associate managing editor, argued about how we expect professionals in all sorts of fields to put their personal opinions aside when they do their work. Why would we expect less of journalists?

As a journalist, what should we do? Maybe we should remember our goal is to inform readers about issues and events so that our audience can make their own opinions about topics based on facts.